Asia Pacific Values Survey

|

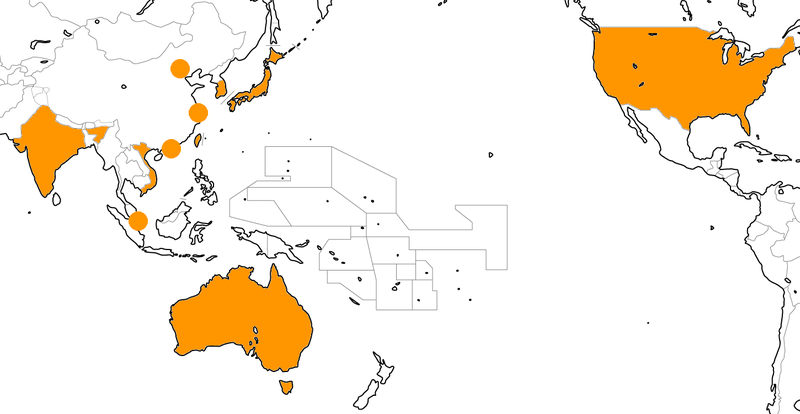

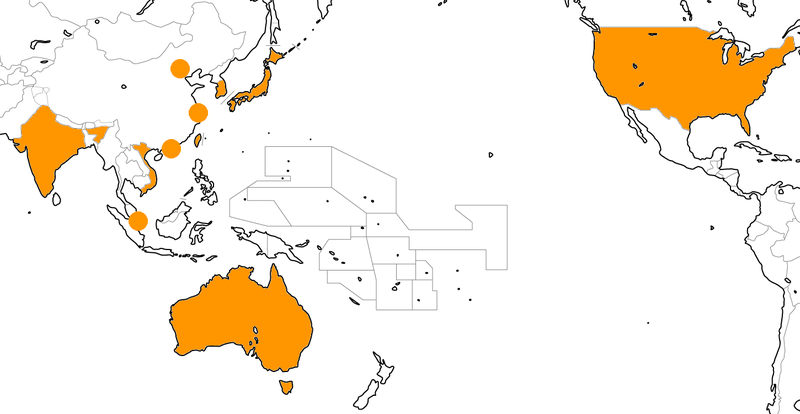

Please click upper links or areas on this map.

Back

Asia Pacific Values Survey

1. Introduction

This is the the website of gthe Asia-Pacific Values Surveyh (2010-2014 fiscal years) by the cross-national survey team of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics (Chief Ryozo Yoshino), with the financial support by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS): Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) No.22223006. We are developing this study in order to exemplify practical research of a new methodology for cross-national comparative survey, called CULMAN (Cultural Manifold Analysis) (Yoshino, 2005, 2014; Yoshino, Nikaido & Fujita, 2009). It is part of the broader research project that is meant to build on and expand the two predecessor projects: the East Asia Values Survey (2002-2005), and the Pacific-Rim Values Survey (2006-2009). In 2010, we conducted fieldwork for the surveys in Japan and the United States, in three locations of the mainland China (Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong) and Taiwan in 2011, Australia, Singapore and South Korea in 2012, and India and Vietnam in 2013. We carried out these surveys, using the statistical random sampling method appropriate for each location and through face-to-face interviews.

As far as the methodology of public opinion survey is concerned, we have confirmed that the Japanese has an advantage to realize statistically the most rigid and democratic (one vote for each electorate) survey in the world, simply because the census data are reliable and the registration list of all voters and all residents are available for public opinion survey for the government and academic research.

We kept in our mind, however, that we should learn as to the methodology of public opinion survey carried out in each country, rather than imposing the Japanese way upon the other countries. The result of public opinion survey more or less influences each countryfs economy and politics, whether each country can carry out is statistically rigid survey or not. Thus, we believe that each countryfs methodology of public opinion survey and its degree of statistical rigidity itself show their economic, political and social conditions, including the degree of democracy.

This brief monograph gives some historical background of the study. On the other hand, we would like to refer readers to Yoshino (2001, 2005c, 2006, 2009, 2014), Yoshino & Hayashi (2001), Yoshino, Nikaido & Fujita (2009), and Yoshino, Shibai, Nikaido & Fujita ( in preparation) for more detailed English explanation on the methodologies such as back-translation technique for questionnaire and statistical random sampling, a paradigm of cross-national comparability, etc. As for the information on our past surveys, see a series of ISM Research Reports published over decades, or our home page of the Institute of Statistical mathematics.

1) http://www.ism.ac.jp/~yoshino/corrigenda_e.html for Corrigenda.

2) http://www.ism.ac.jp/~yoshino/index_e.html for our cross-national surveys.

3) http://www.ism.ac.jp/editsec/kenripo/index.html The ISM Survey Research Report.

4) http://www.ism.ac.jp/editsec/kenripo/index_e.html (in English)

5) http://www.ism.ac.jp/ism_info_j/kokuminsei.html The webpage of ISM survey.

6) http://www.ism.ac.jp/ism_info_e/kokuminsei_e.html (in English)

Although our questionnaire covers various topics of daily life, the questionnaire of the APVS includes the following items.

EItems on Sense of TrustEE Q22, 24(Social Supportj, Q55 (Social Participationj,

@@@@@Q2, 3 Friendships between states [public opinion & real intension],

@@@@@Q36, 37, 38iGSS 3 items on interpersonal trustj,

@@@@@Q52iWVS items on Trust on Organization & Science and Technologyj

EItems on the Reason to LiveEEE Q8, 51

EItems related to hGhost Surveyh (interest on mystery) EEE Q26, 33, 39,

2. Some History on Our National Character Survey

The Institute of Statistical Mathematics (ISM) has been conducting a longitudinal nationwide social survey on the Japanese national character every five years since 1953, using the same questionnaire items (Mizuno et al., 1992). The survey is called gNihonjin no Kokuminsei Chosah (Japanese National Character Survey). Although definition of the term gnational characterh may be very problematic, here it simply means the characteristic shown in peoplefs response patterns to a questionnaire survey (Hayashi et al., 1998; cf. Inkeles, 1997). The question items cover various aspects of peoplefs opinions about their culture and daily life. This survey was one of the foundations of the public opinion survey system based on the statistical sampling theory developed immediately after World War II in Japan. The significance of this survey was clear at the time when Japan was expected to shift from the military regime to a democratic system in the latter half of 1940s (Yoshino, 1994). This survey stimulated many countries to carry out the same sort of time series surveys such as the World Values Survey, Eurobarometer, General Social Survey (GSS) of USA, ALLBUS of Germany, CREDOC of France, etc. (There was a time that the post-war Japanese democracy had been criticized because it was not democratic from a viewpoint of the Western world. Interestingly, however, Japan conducts public-opinion polls based on statistically ideal sampling using an almost complete residential or votersf list whereas the other countries have to use other methods such as quota sampling or random-route sampling. The latter two sampling methods consider statistical randomness but do not yield the statistical estimate of sampling errors. As far as the system of public-opinion polls is concerned, therefore, Japan may be more democratic than the Western countries in the sense of inclusiveness and representativeness.)

Since 1971, the survey of ISM has been extended to a cross-national comparative study for more advanced understanding of Japanese national character (Hayashi, 1973). The focus of our cross-national surveys is the investigation of the statistical comparison of peoplesf social values and their ways of thinking and feeling. More explicitly, our concern has been with cultural identities and peoplefs attitudes toward economy, freedom of speech, interpersonal relationships, leadership, politics, public acceptance of science and technology, religion, social security, etc. These aspects may clarify certain similarities or dissimilarities that are represented by psychological distances between countries or races in certain statistical pattern analyses of responses (Hayashi, 2001a, 2001b; Hayashi et al., 1998; Yoshino, 1994, 2001c).

Table 1DList of the Main Past Surveys on National Character by the Institute of Statistical Mathematics.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1953 - present Japanese National Character Survey (every five years)

1971 Americans of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii

1978 Honolulu residents, Americans in Mainland USA

1983 Honolulu residents

1988 Honolulu residents

1987-1993 Seven Country Survey

1987 Britain, Germany & France

1988 Americans in Mainland USA, Japanese in Japan

1992 Italy

1993 The Netherlands

1991-1999 Recent Overseas Japanese Surveys

1991 Brazilians of Japanese ancestry in Brazil

1998 Americans of Japanese ancestry on the U.S. West Coast.

1999 Honolulu residents in Hawaii

2002-2005 East Asia Values Survey

(Japan, China [Beijing, Shanghai], Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, & Singapore)

2004-2009 The Pacific-Rim Values Survey (1st round of The Asia-Pacific Values Survey)

(Japan, China [Beijing, Shanghai], Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, USA, Singapore, Australia & India)

2010-2014 The Asia-Pacific Values Survey (2nd round)

(Japan, China [Beijing, Shanghai], Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, USA, Singapore, Australia, India & Vietnam)

@@2010 Japan & USA

@@2011 China (Beijing, Shanghai, & Hong Kong) and Taiwan

@@2012 Singapore, Australia, & South Korea

@@2013 India, Vietnam

@@2014 Japan (omnibus), USA (CATI, omnibus)

(All of these are face-to-face surveys based on nationwide statistical random sampling data, except for Hawaii, Brazil, Mainland China, i.e., Beijing and Shanghai [urban areas only]), Australia [Queensland, New South Wales, & Victoria]), and India [10 major cities].) Note: Although the Japanese title of the survey project 2004-2009 literally means the Pacific-Rim Values Survey, the title gThe Asia-Pacific Values Surveyh was occasionally used for the project in the past English publication, because it covered not only Pacific-Rim Area but India. From now on, we designate the Pacific-Rim Values Survey (effectively 1st round of the Asia-Pacific Values Survey) for the 2004-2009 project and the Asia-Pacific Values Survey for the 2010-2014 project (effectively 2nd round the Asia-Pacific Values Survey).

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The cross-national survey, however, involves particular methodological problems. It is not simple to compare response data collected under different conditions. Different countries may use the same questionnaire but in different languages and employ different statistical sampling methods as well. There is no a priori knowledge as to how these different conditions influence peoplesf responses even in the case where there is no substantive difference of opinions and social values between peoples (Yoshino, 2001c). Thus, an important problem of our study is to investigate those conditions under which meaningful cross-national comparability of social survey data is guaranteed. As our approach towards this problem over decades, we have been developing the methodology called CLA (cultural link analysis). The main components of CLA are 1) a spatial link for cross-national comparison, 2) a temporal link inherent in longitudinal analysis, and 3) an item-structure link inherent in the commonalties and differences in item response patterns within and across different cultures (cf. Guttman, 1972). In CLA we utilize, for example, the back-translation technique and statistical pattern analyses such as Hayashifs Quantification Method (Hayashi, 1992) or Yoshinofs (1992a, 1992b, 1994, 2001c) Super-culture Model. The utilization of those pattern analyses consists of an important part of our methodology. Namely, although a simple cross-national tabulation of peoplefs responses with respect to a single item may not be reliable because peoplefs responses may occasionally be sensitive to slight differences in the wording of certain questions, certain pattern analyses or scaling on a set of items can be reliable. (See Yoshino & Hayashi [2002] for an overview on our approach.)

On the other hand, in this cross-national study, we have found some response tendencies particular to certain countries. For example, the Japanese tend to avoid polar answer categories and to choose intermediate categories, whereas the French generally tend to give negative responses to any question. (Here I may be exaggerating these tendencies to make the points clearer.) I think that we should consider these response tendencies when we analyze not only peoplefs sense of trust but public opinion polls or social survey data in general. See Hayashi (2001a, 2001b), Hayashi et al. (1998), Yoshino (1994, 2001c, 2002, 2005, 2006, 2009), Yoshino & Hayashi (2002), Yoshino, Nikaido & Fujita (2009), and Yoshino, Hayashi & Yamaoka (2010) for results of our cross-national surveys.

3. Japanese national character survey (1953-present)

Our longitudinal survey of Japanese national character shows some stable aspects of attitudes and social values of the Japanese (Hayashi & Kuroda, 1997; Yoshino, 1994). Among others, the stability of certain interpersonal attitudes and religious attitudes may distinguish the Japanese from other countries. Namely, the Japanese show a higher score on the gGiri-Ninjyo (a sort of conflict between obligation and heart) scaleh than the other countries. Moreover, while only one third of the Japanese have religious faith, but more than 60% of the Japanese support the opinion that religious attitudes are important (Yoshino & Hayashi, 2002; Yamaoka, 2000).

I will briefly explain certain fundamental dimensions of the Japanese social values as follows.

Fundamental dimensions of the Japanese social values

Hayashi (1993) has identified two important dimensions that underlie the Japanese national character in the survey. That is, 1) the dimension of interpersonal relationships (gGiri-Ninjyoh attitude, or a complicated sense of humanity and obligation that is particular to the Japanese interpersonal relationships) and 2) the dimension of a modern-traditional contrast in their way of thinking. On one hand, as mentioned before, the Japanese interpersonal attitude has been stable, at least over the last half century, and probably for much longer than our longitudinal survey. This corresponds to the first dimension. On the other hand, for over 100 years since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan has been doing her best to overtake Western science and technology and to develop it into a Japanese adaptation. Probably this enduring effort has underlined the dimension of the tradition vs. modernity orientation in the Japanese way of thinking.

However, the Japanese way of thinking has been gradually changing, and there appeared a generation gap between people of 20-24 years old and those older than 25 years in our survey of 1978 (note that the younger generation was born more than 10 years after the end of World War II. In 1956, the economic white paper declared, gJapan is no longer in the post-war condition,h and this symbolized the start of the high-speed development of industry and economy. On the other hand, however, Japan had to face many social problems concerning pollution because of the high-speed industrialization around 1970. Since the signs of the younger generationfs changes appeared as early as 1978, their current way of thinking has become more complicated than ever.

Furthermore, the Japanese have been in the confusion of the transition period from the established social system to a system of a highly advanced information age. In this confusion, a Central Research Services, Inc. (2000) survey reported the majority of Japanese peoplefs distrust toward traditional systems such as banking, bureaucracy, as well as of congressmen, police, etc., in spite of the stereotype of the Japanese as a highly trustful nation (Fukuyama, 1995).

4. The World as a Cultural Manifold

The 20th century was the time of expansion of Western civilization. Differences of cultures occasionally prevented us from our understanding each other. In this time of globalization, I would like to emphasize the fact that there are various ways of successful social development, therefore, we should not impose onefs own social value on any other country if we intend to develop a peaceful world.

The globalization necessarily changes some institutional systems and customs towards more universal ones under the influences of transnational exchange or trade. On the other hand, some other systems are becoming more and more sensitive to cultural differences, as a reaction to the globalization.

In order to facilitate the mutual understanding between the East and the West, we need to keep in mind the differences of social values between them. The study on the scale of trust (Yoshino, 2005, 2006, 2008) may caution us on the applicability of a certain gsingleh scale invented by the Western cultures to the Eastern cultures, or vice versa. For example, it is not always the case in Asia that gthe distrust is a culture of povertyh as Banfield (1958) once mentioned. A Chinese proverb says that gFine manners need a full stomachh (or gThe belly has no earsh), but another says gBe contended with honest poverty.h Gallup (1977, p.461) reported that they could not find a very poor but still happy people in their global survey. I think that they missed the reality. For example, Brazilians were very optimistic even when Brazil fell down to the worst debtor nation in the world (Inkeles, 1997) Inglehart reported a correlation of .57 between economic development and life satisfaction for some 20 countries surveyed in 1980s (Inkeles, 1997, pp. 366-371). But the life satisfaction of Japan in the 1980fs was lower than the years around 2000, although Japan was close to the top of the world economy in those days and now she has sufferred from depression over two decades. Thus, we need scales constructed from various perspectives of social values in order to understand various cultures in the age of globalization.

Although China had so many battles between small countries (within the area corresponding to the modern China) over thousands of years in their history, once they were synthesized as a large empire such as Tang Dynasty, their government employed peoples of various races as high-class bureaucrats. This used to be the main factor to successfully develop and maintain a large empire and their culture, often over centuries. This is analogous to the Roman Empire, but it is contrastive to the modern Western countries (and Japan during WWII) that colonized Asian and African countries in the 19th and 20th centuries. The history shows that trust between different races changes according to social conditions in the short run, although it is relatively stable over time.

After our previous China survey (China 2001 survey [Yoshino, 2006]), there occurred the problem of SARS spreading from Guang-Zhou in China. People inside and outside of China criticized the local governments, suspecting that they attempted to hide the serious conditions. This seems to suggest a significant change of China, from secretive attitude to more open attitude for every matter. The secretive attitude was linked to the system of severe punishment on political responsibility. The open attitude is a key to democracy that is necessary for successful capitalism. The then mayor of Beijing got fired because of his mishandling of SARS. The government started encouraging people to inform of the presence of patients. This situation seems to show that China is changing rapidly, but in a Chinese way. Here it may be important to quote Dogan (2000)fs statementg... Erosion of confidence is first of all a sign of political maturity. It is not so much that democracy has deteriorated, but rather the critical spirit of most citizens has improved...h

In spite of still prevailing confusion in East Asia (actually in the entire world), I hope that East Asia will advance towards the peaceful development without serious conflicts. For the mutual understanding among Asian countries, one should keep in mind their ways of thinking such as gMentsu (face)h and gHonne and Tatemae (a difference between words and actual intensions)h of the Chinese, the Japanese, and the Korean. This is also the case with the Asian countries for their understanding of the West.

Once upon a time, Weber (1904-05) argued that Asian countries were not able to develop capitalism in his theory on religion and capitalism. Now we know so many counter-examples such as Japan, Korea, NIES, and China, against his argument. Some people argued that the Japanese adaptation of Confucius philosophy adapted to Japan functioned as a replacement of Protestant ethics and led Japan to a successful development of capitalism (Morishima, 1984). But the past decades have seen many examples to show that economic success is not linked to a particular ethics, ideology or religion. Now we have more and more data to consider the relationships between economic development, social systems and social values because of the rapid change of social systems in many countries of the world than before.

In 2010 spring, we started a new project gThe Asia-Pacific Values Surveyh and carried out a nationwide face-to-face survey in Japan and USA during November of 2010 to January of 2011. Finally this project has covered all the countries and areas of the previous project gPacific-Rim Values Surveyh, and Vietnam also. (Originally we intended to cover more countries in the South-East Asia, but we have not made it because of difficulties which we faced some political and technical problems in order to carry out statistically rigorous sampling surveys by face-to-face interview.)

We are still struggling on data analyses. For some recent analyses, see a special issue on

Bahaviormetrika, 42, 2.

I hope that our survey data will be helpful for further constructive arguments, and the mutual understanding for the peaceful development and economic prosperity of the world.

Ryozo Yoshino

Note 1: For more updated explanation of the history of our surveys and our methodology, see the forthcoming papers of special issue of Bahaviormetrika, among others, Yoshino, Shibai, Nikaido & Fujita (2015, in preparation) and Yoshino (2015, in preparation).

Note 2: In each country we have employed an area sampling method that accommodates the specific circumstances and conditions therein, which does differ from the kind of random sampling method used in Japan based as it is on the national residential registry system. It is important for the researchers to grasp the nature of the ground-level operations of actual surveys as they happened, as real-life practice could differ from plans on paper. While we believe this to be no different in Japan too, but the local survey research operators tend to conceal information to the client (i.e., the ISM), both because the relaying of such minute details can be cumbersome, and that it is conceptually difficult to legitimatize any discrepancy between theory and actual practice. As far as possible we have goaded the local survey operators to explain and clarify the relations between theory and their actual practice, while appreciating their efforts to overcome the practical and logistical difficulties of carrying out a survey research project. We like to note that there are many revelations and insights that have come to us only in our second and third attempts at survey research in the three countries. We have been reintroduced to the importance of being sensitive to the discrepancy between theory and practice.

Note 3: In the case we find some errors in our reports or data, we will list them in our home page: http://www.ism.ac.jp/~yoshino/corrigenda_e.html, where you can see our past surveys too.

Acknowledgement

This study is financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS): Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) No.22223006. We are very grateful for their support over years.

References@https://www.jsps.go.jp/j-grantsinaid/12_kiban/ichiran_22/e-data/e33_yoshino.pdf

Back

Data Archives

Data Archives Asia Pacific Values Survey 2010-14

Asia Pacific Values Survey 2010-14 Pacific Rim Value Survey 2004-09

Pacific Rim Value Survey 2004-09 East Asian Value Survey 2002-05

East Asian Value Survey 2002-05 Cross-National Survey in East Asia

Cross-National Survey in East Asia Hawaii (including Japanese-American)

Hawaii (including Japanese-American)  Japanese-American living in the West Coast of the US 1998-99

Japanese-American living in the West Coast of the US 1998-99 Research on National Character of Japanese-Brazilian 1991-92

Research on National Character of Japanese-Brazilian 1991-92 Cross-National Survey of Seven Countries

Cross-National Survey of Seven Countries Hawaiian (including Japanese-American) living in the Mainland of US 1978-83

Hawaiian (including Japanese-American) living in the Mainland of US 1978-83 Japanese-American living in Hawaii 1971

Japanese-American living in Hawaii 1971 Study on the Japanese National Character

Study on the Japanese National Character Others: Omnibus Survey, Web Survey Comparative Experiment, etc.

Others: Omnibus Survey, Web Survey Comparative Experiment, etc. Corrigenda

Corrigenda References

References